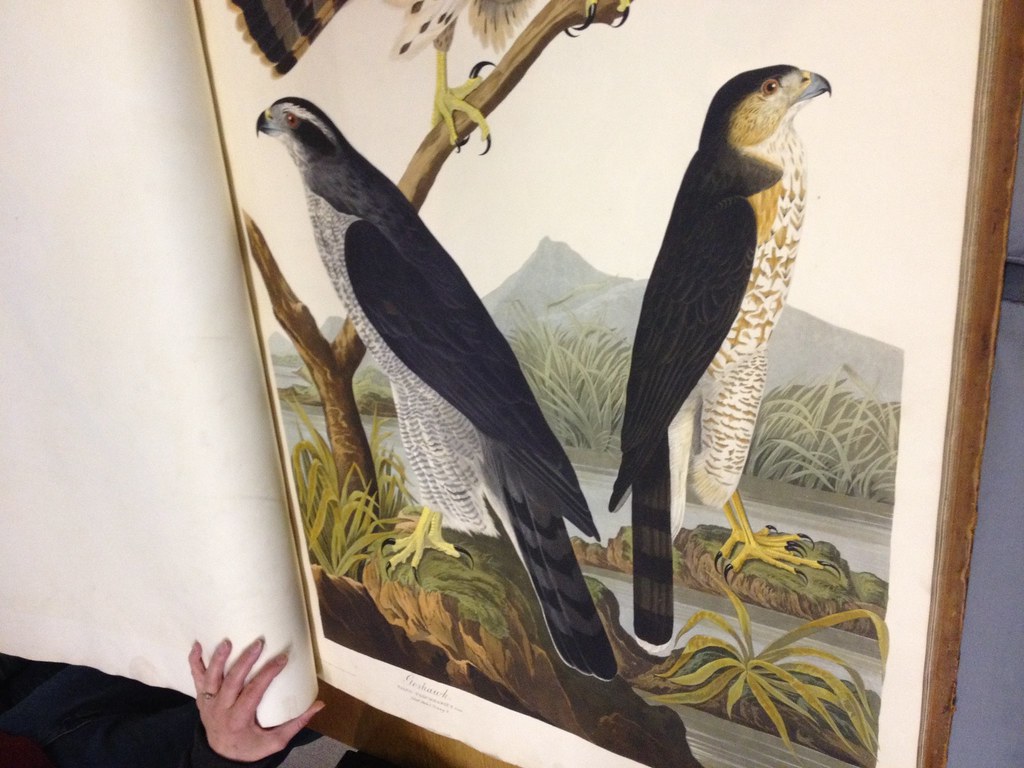

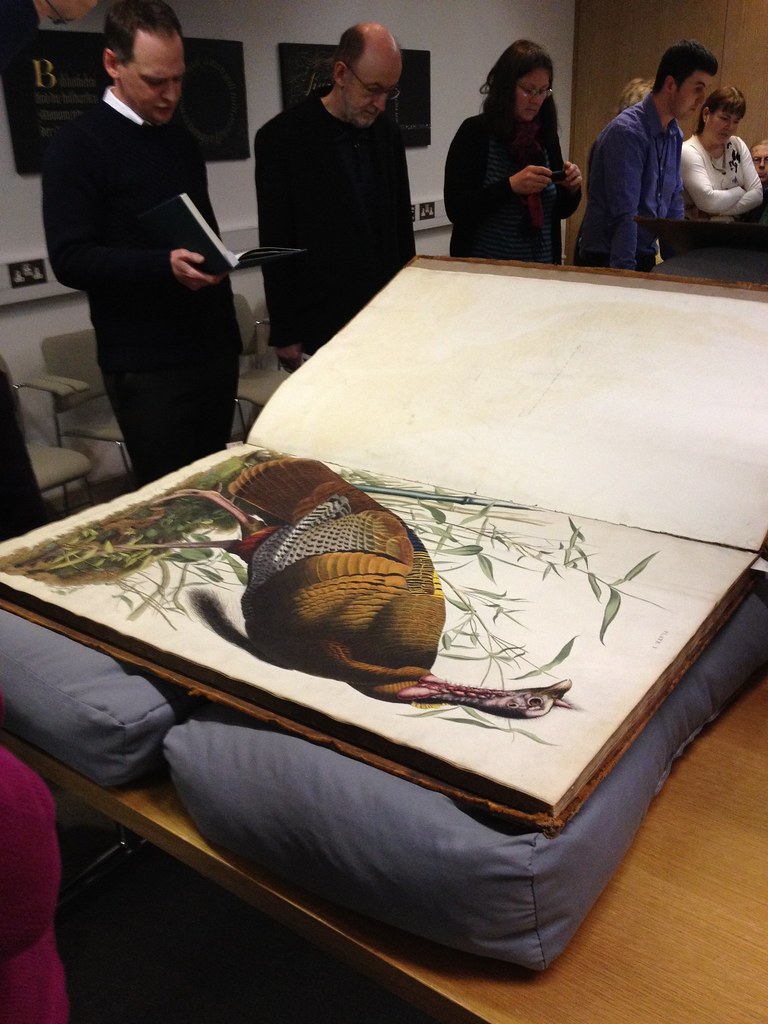

Twenty of us gathered round five tables pushed together at the University Library. On the tables: two volumes of John James Audubon's

Birds of America, published between 1827 and 1838.

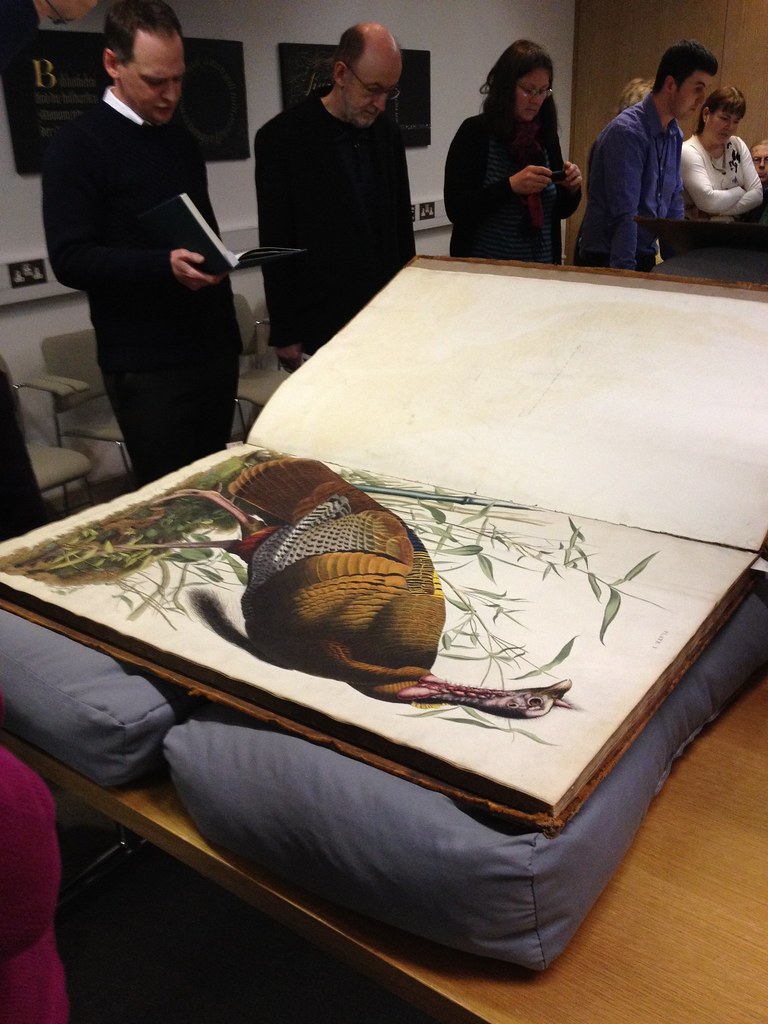

These books are extremely rare (only 200 or so copies exist), extremely fragile (ordinary readers cannot usually ask to see them), and extremely huge. It takes two assistants to turn the pages, and each time they do so, the paper crackles. The size is called 'double elephant folio' -- a very unusual and very expensive format.

Ed Potten, Head of Rare Books at the Cambridge University Library, gave a brilliant talk on the books. Here's what I learned:

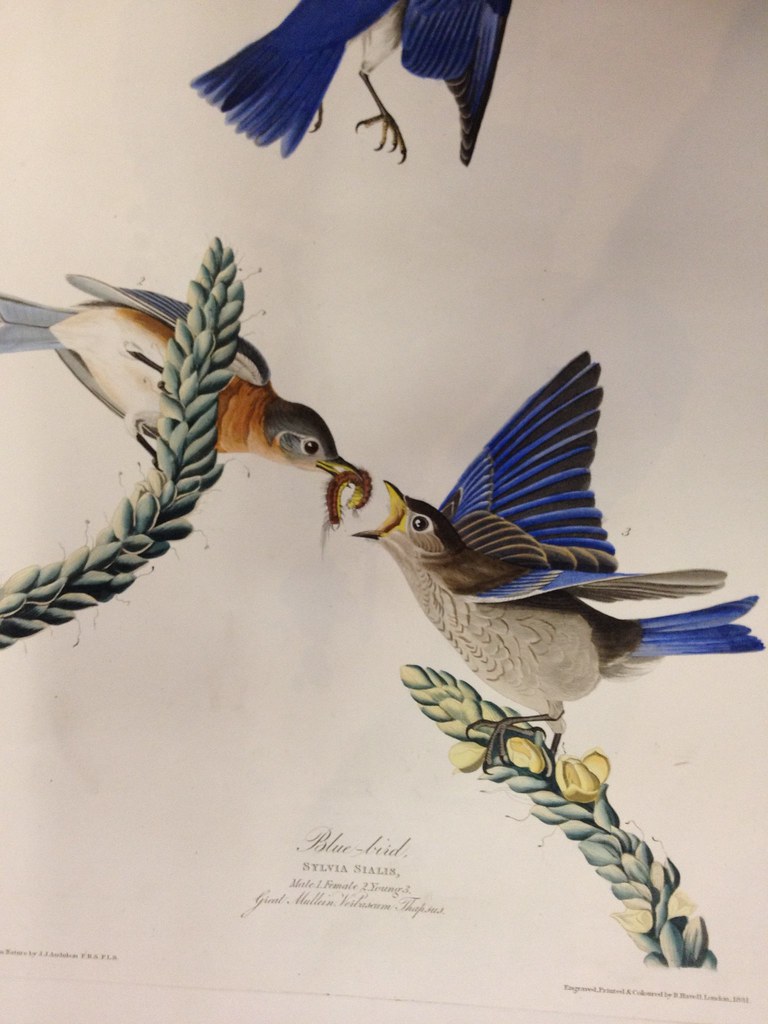

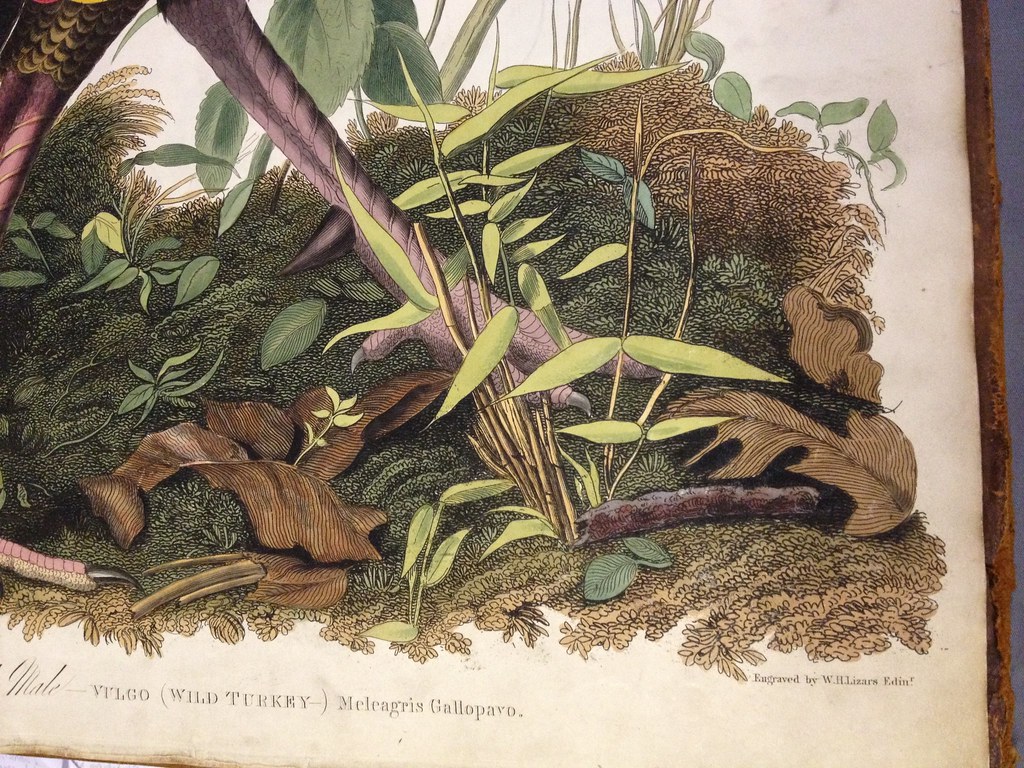

The Birds of America contains 435 plates in total. Each plate is based on a watercolour painting by Audubon. The watercolours were initially engraved onto copper plates by the renowned Edinborough firm of

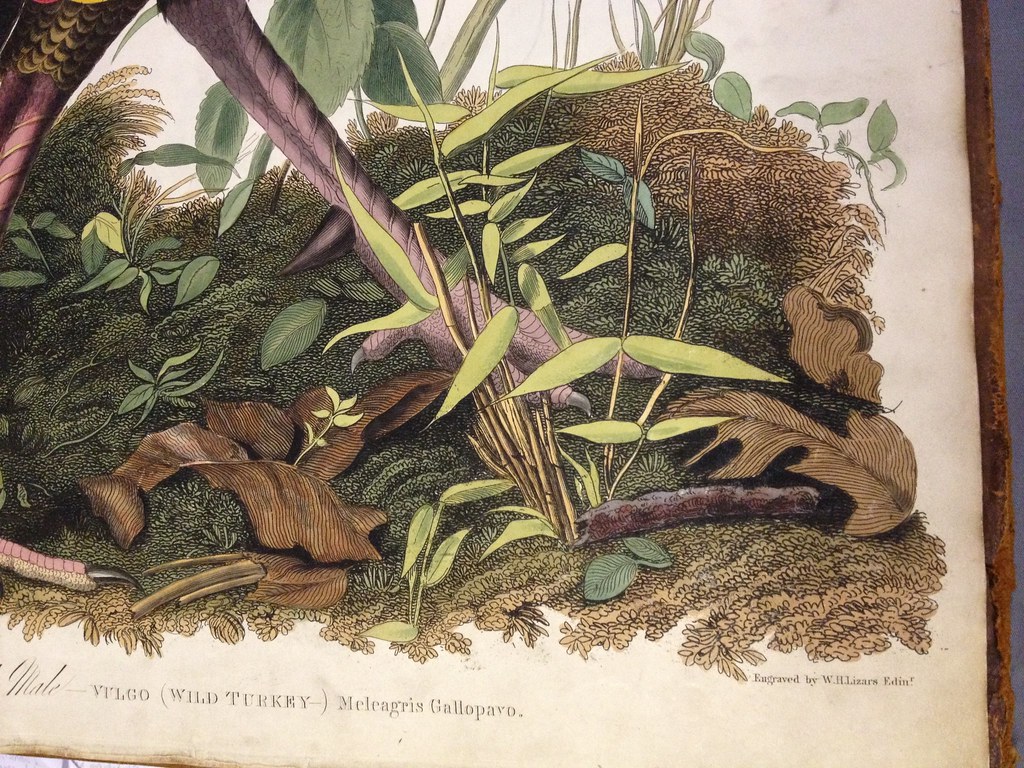

W.H. Lizars. But most of the watercolours were transferred to print by the London printers

R. Havell & Son who used the newly rediscovered

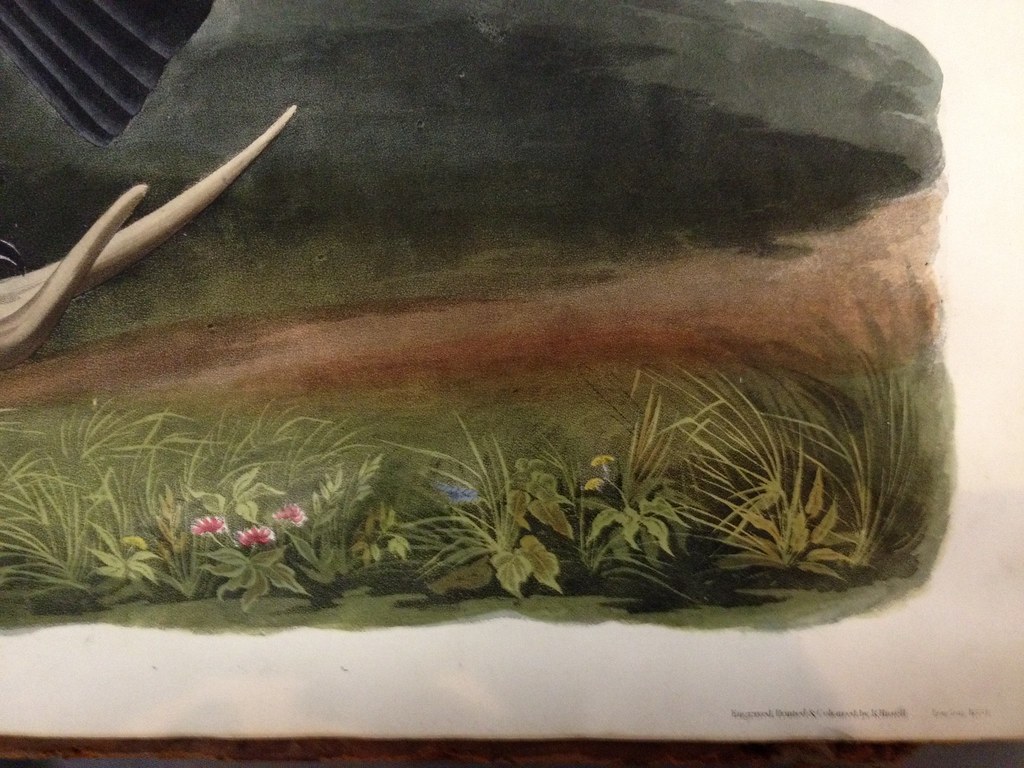

aquatint process. The 13-year-old John Mason painted 50 of the background scenes.

|

| Ed Potton reads out information about Audubon. The volume is opened to the turkey page: the bird is life size! |

|

| At bottom right, it reads 'Engraved by W.H. Lizars Edin' |

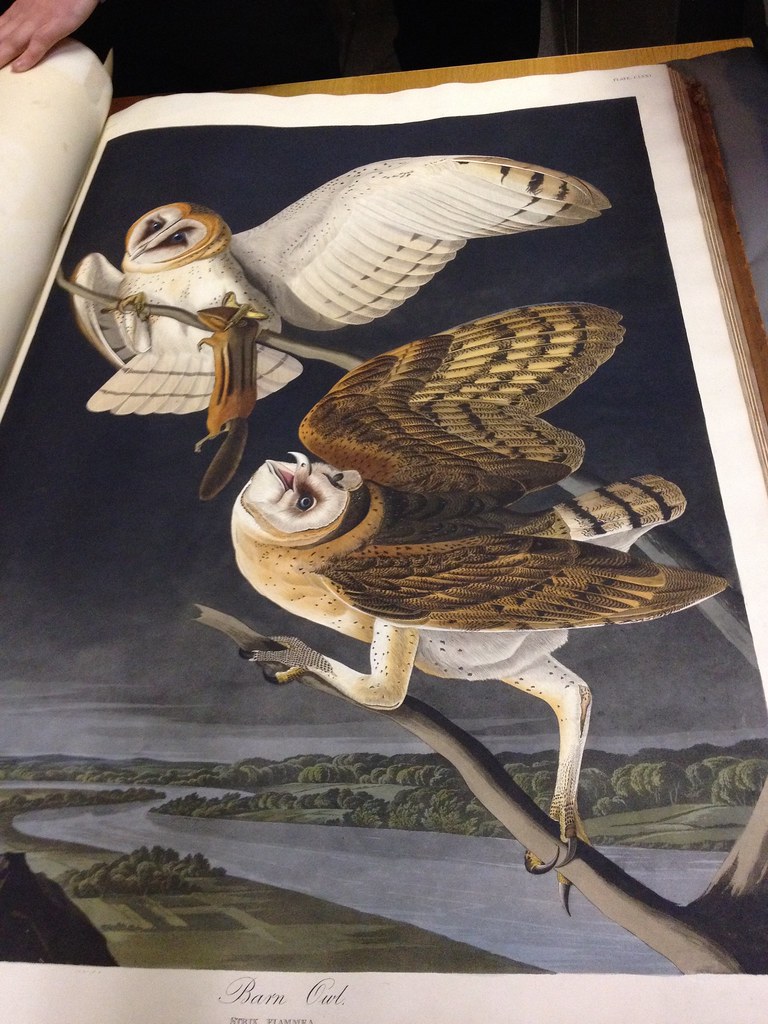

Each plate is hand-coloured with watercolour. This means that all the copies differ slightly from each other.

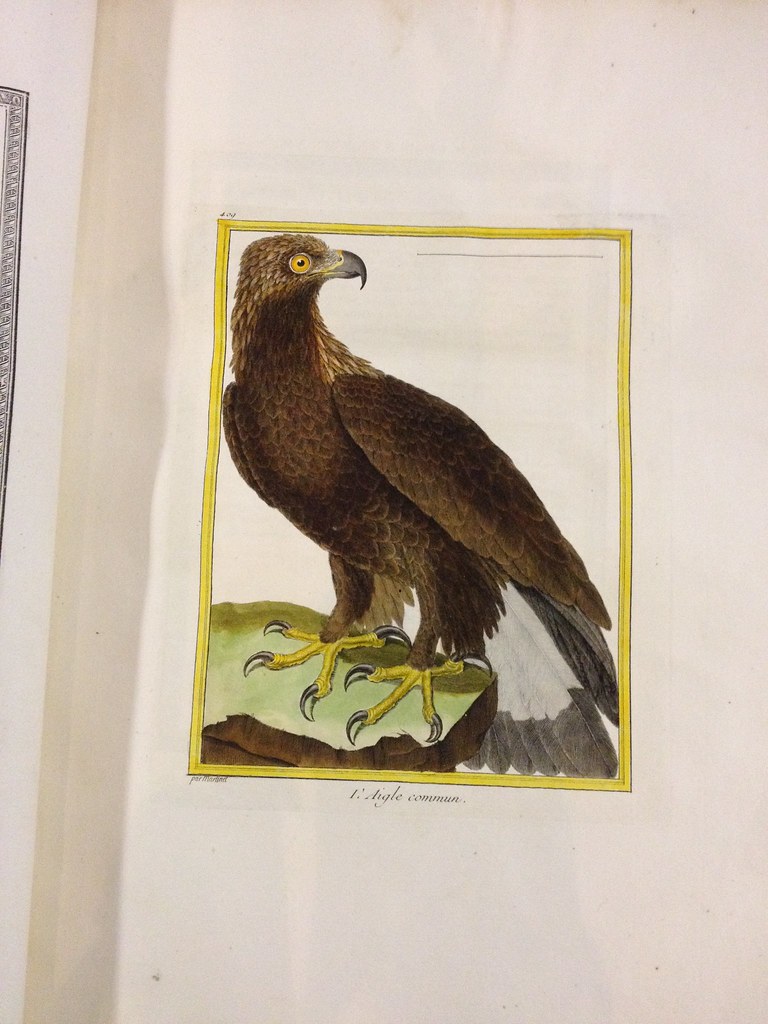

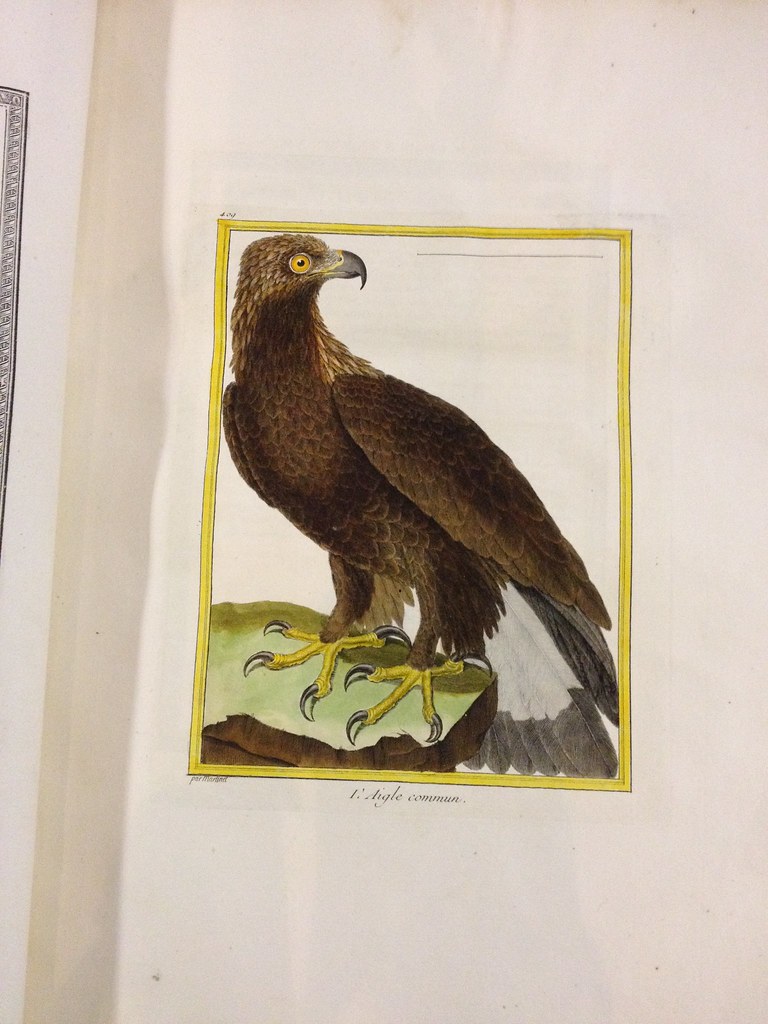

Ed Potten opened an earlier book for us to show us how Audubon revolutionised wildlife illustration. This

Histoire naturelle des oiseaux (1771) shows

static birds:

|

| From the 1771 Histoire naturelle des oiseaux (Natural History of Birds) |

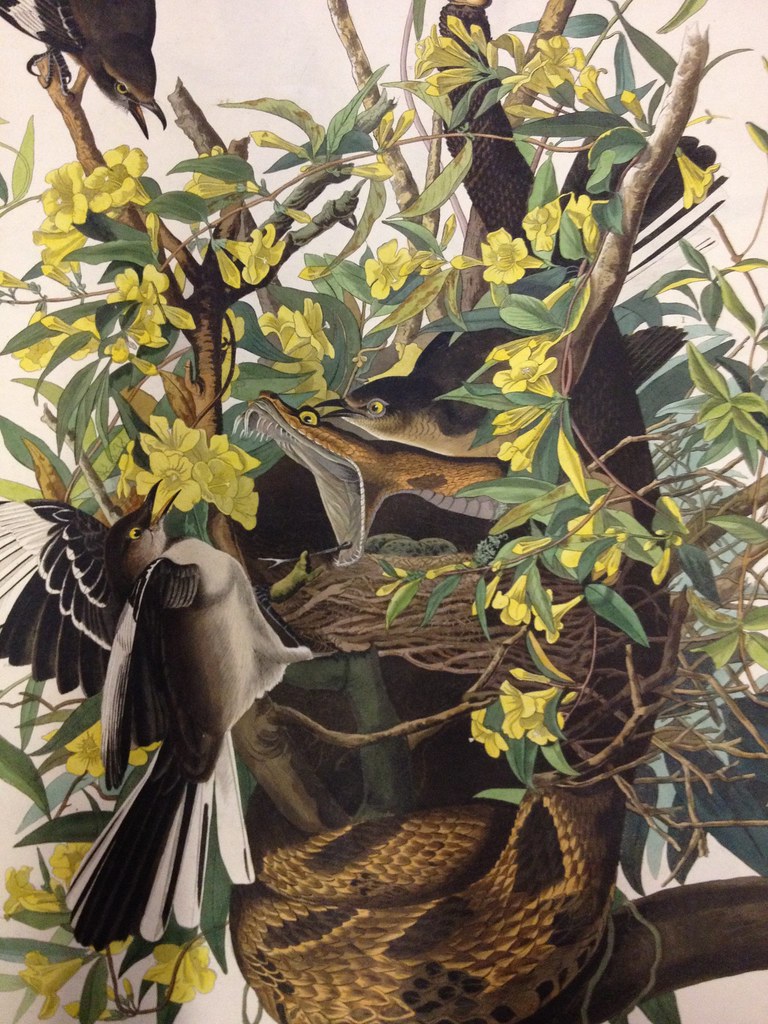

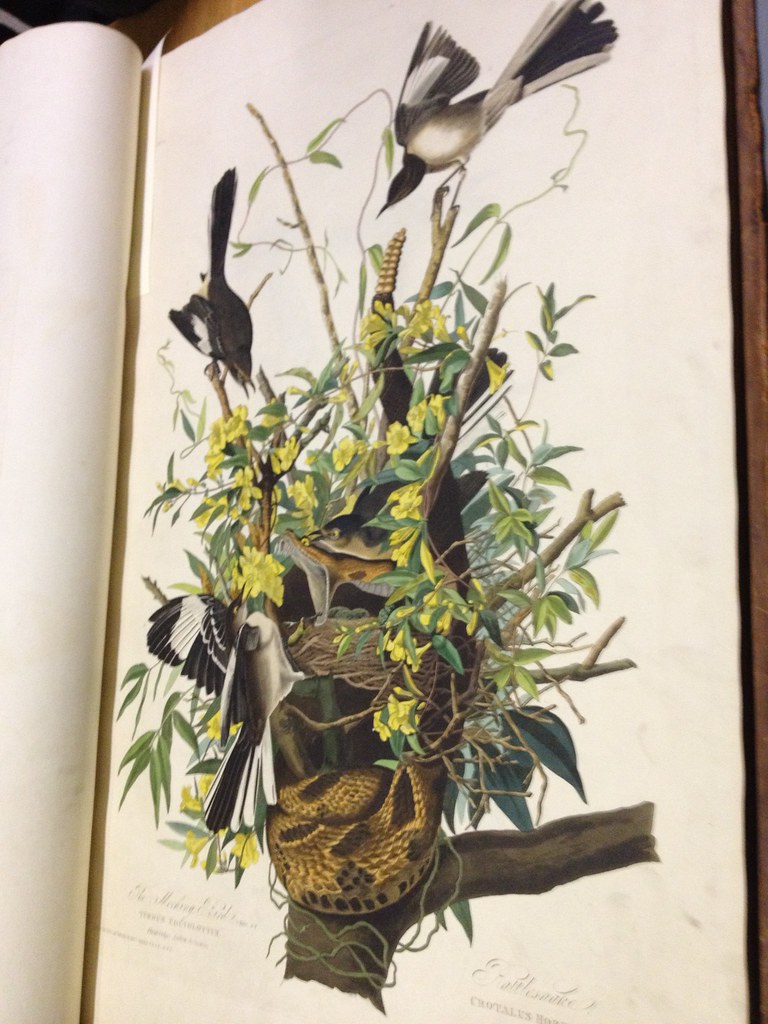

By contrast, Audubon's illustrations are action-packed. Here a rattlesnake attacks a mockingbirds' nest. He has turned 'scientific' imagery into an exciting story.

Critics complained that such scenes were not realistic. How would a rattlesnake manage to climb up so high?

But it's a bit like

the dinosaur art at the Sedgwick Museum: ultimately, we don't care that it's not realistic. We want drama and beauty in our art.

It's odd that Audubon's plates are so dynamic -- considering that he did them from

dead birds. Audubon collected his specimens by going out and

shooting them. It wasn't unusual for him to come home with 50 dead birds in a day.

He then dissected and stuffed the birds. His studio was crammed full of these stuffed birds. One visitor noted that Audubon's house smelled of "dead meat".

Audubon's watercolours still exist: the New York Historical Society owns them. The copper plates, though, were destroyed in a fire. The Birds of America was a publishing sensation, and the smaller version of it a bestseller.

What a privilege to have seen these lavish, rare (and completely insane) objects of material beauty. Thank you, Cambridge Festival of Science!

More information:

The Birds of America page at Wikipedia

The Birds of America page at the National History Museum (London)

More at this blog:

Arty events at the Science Festival

Permalink: http://artincambridge.blogspot.com/2013/03/audubons-birds-of-america-in-cambridge.html